In the early 19th century, the United States felt threatened by England and Spain, who held land in the western continent.� At the same time, American settlers clamored for more land.� Thomas Jefferson proposed the creation of a buffer zone between US and European holdings; to be inhabited by eastern American Indians.� This plan would also allow for American expansion westward from the original colonies to the Mississippi River.

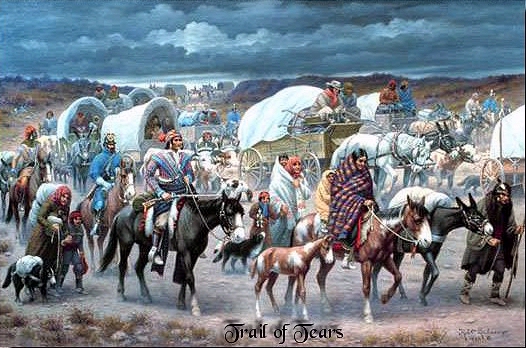

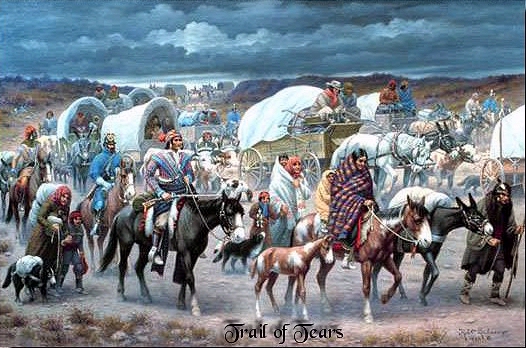

Between 1816 and 1840, tribes located between the original states and the Mississippi River (including Cherokee's, Chickasaw's, Choctaw's, Creek's, and Seminole's) signed more than 40 treaties ceding their lands to the US.� In his 1829 inaugural address, President Andrew Jackson set a policy to relocate eastern Indians.� In 1830, it was endorsed, when Congress passed the Indian Removal Act to force those remaining to move west of the Mississippi.� Between 1830 and 1850, about 100,000 Native Americans living between Michigan, Louisiana, and Florida moved west after the US government coerced treaties or used the US Army against those resisting.� Many were treated brutally.� An estimated 3,500 Cree's died in Alabama and on their westward journey.� Some were transported in chains.

Historically, Cherokee's occupied lands in several southeastern states.� As European settlers arrived, Cherokee's traded and intermarried with them.� They began to adopt European customs and gradually turned to an agricultural economy; while being pressured to give up traditional homelands.� Between 1721 and 1819, 90 percent of their lands were ceded to others.� By the 1820's, Sequoyah's syllabary brought literacy and a formal governing system with a written constitution.� In 1830 (the same year the Indian Removal Act was passed), gold was found� on Cherokee lands.� Georgia held lotteries to give Cherokee land and gold rights to whites.� Cherokee's were not allowed to conduct tribal business, contract, testify in courts against whites, or mine for gold.

The Cherokee's successfully challenged Georgia in the US Supreme Court.� President Jackson, when hearing of the Court's decision, reportedly said, "[Chief Justice] John Marshall has made his decision; let him enforce it now if he can."

Most Cherokee's opposed removal.� Yet a minority felt that it was futile to continue to fight.� They believed that they might survive as a people only if they signed a treaty with the US.� In December 1835, the US sought out this minority to effect a treaty at New Echota, Georgia.� Only 300 to 500 Cherokee's were there; none were elected officials of the Cherokee Nation.� Twenty signed the treaty, ceding all Cherokee territory east of the Mississippi to the US in exchange for $5 million and new homelands in Indian Territory.� More than 15,000 Cherokee's protested the illegal treaty.� Yet, on May 23, 1836, the Treaty of New Echota was ratified by the US Senate - by just one vote.

Most Cherokee's, including Chief John Ross, did not believe that they would be forced to move.� In May, 1838, Federal troops and state militias began the roundup of the Cherokee's into stockades.� In spite of warnings to troops to treat the Cherokee's kindly, the roundup proved harrowing.

Families were separated.� The elderly and sick forced out at gunpoint.� People were given only moments to collect cherished possessions.� Looters followed, ransacking homesteads as Cherokee's were led away.

Three groups left in the summer, traveling from present day Chattanooga by rail, boat, and wagon, primarily on the Water Route.� But river levels were too low for navigation; one group, traveling overland in Arkansas, suffered three to five deaths each day due to illness and drought.

Fifteen thousand captives still awaited removal.� Crowding, poor sanitation, and drought made them miserable.�� Many died.� The Cherokee's asked to postpone removal until the fall, and to voluntarily remove themselves.� The delay was granted, provided they remain in internment camps until travel resumed.

By November, 12 groups of 1,000 each were trudging 800 miles overland to the west.� The last party, including Chief Ross, went by water.� Now, heavy Autumn rains and hundreds of wagons on the muddy route made roads impassable; little grazing and game could be found to supplement meager rations.

Two-thirds of the ill equipped Cherokee's were trapped between the ice bound Ohio and Mississippi Rivers during January.� Although suffering from a cold, Quatie Ross, the Chief's wife, gave her only blanket to a child.� She died of pneumonia at Little Rock.� Some drank stagnant water and succumbed to disease.� One survivor told how his father got sick and died; then his mother; then, one by one, his five brothers and sisters.� "One each day.� Then all are gone."

By March 1839, all survivors had arrived in the west.� No one knows how many died throughout the ordeal, but the trip was especially hard on infants, children, and the elderly.� Missionary doctor Elizur Butler, who accompanied the Cherokee's, estimated that over 4,000 died - nearly a fifth of the Cherokee population.

�

The Cherokee Rose

When the Trail of Tears started, the mothers of the Cherokee were grieving and crying so much, they were unable to help their children survive the journey. The Elders prayed for a sign that would lift the Mother's spirits to give them strength. The next day, a beautiful rose began to grow where each mother's tears fell. The rose is white for their tears; has a gold center to represent the gold taken from the Cherokee lands, and seven leaves on each stem for the seven Cherokee clans. The wild Cherokee Rose grows along the route of the Trail of Tears into eastern Oklahoma today.